Over the past eighteen months, Bangladesh’s universities have experienced a disturbing rise in mob intimidation, public humiliation, physical harassment, and administrative inaction directed toward academic staff. These incidents are not isolated. They reflect a deeper reconfiguration of the relationship between the state and the knowledge system. Describing the situation as mere “campus unrest” masks its structural nature. What is unfolding is a political project designed to weaken academic authority and erode the conditions necessary for intellectual autonomy. The central question is therefore not simply who attacked whom, but whether the state still wants universities to think, or merely to comply.

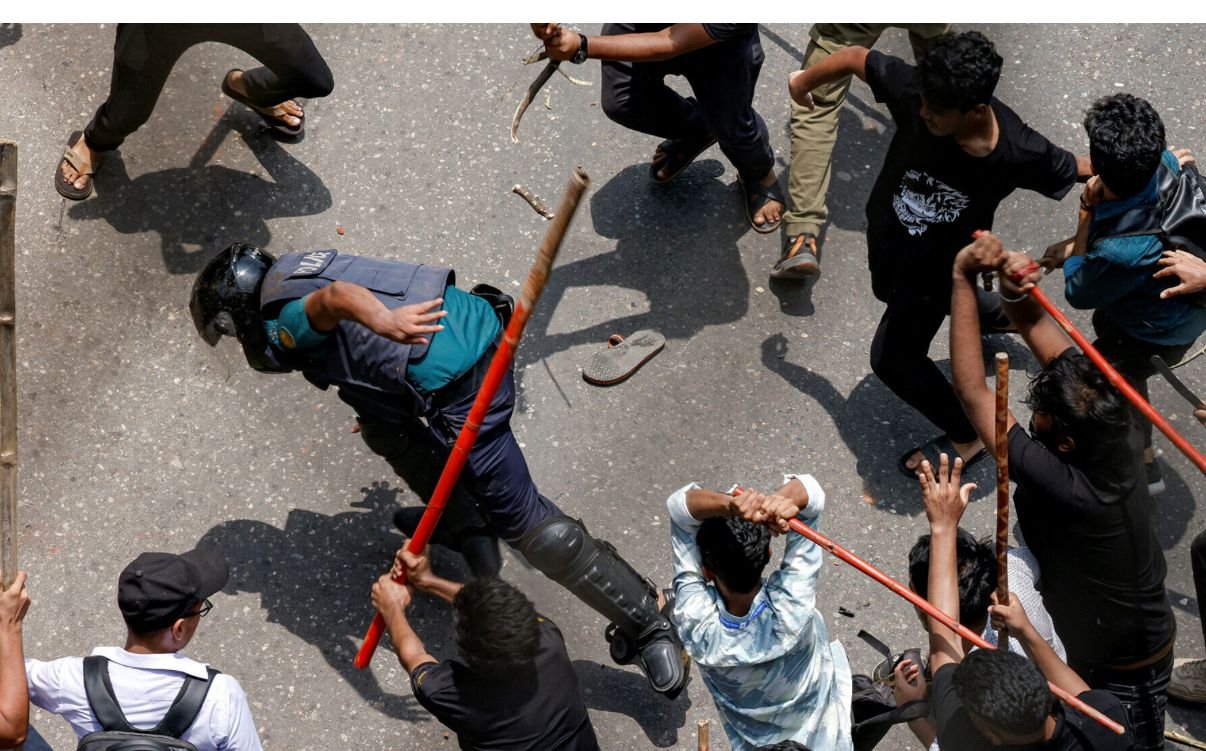

Under the current interim government, this violence has taken on an explicitly political character. Although the state has not imposed direct censorship, it has fostered an environment where mob pressure functions as a key instrument of governance. Repression has been socially outsourced. Mobs now serve as surrogate agents of state power, enacting forms of intimidation and control that the government itself cannot openly justify. Actions that would attract international scrutiny if undertaken directly by the state, violations of academic freedom, freedom of expression, and basic rights, are instead framed as expressions of “public anger,” “religious sentiment,” or “student demands.” This strategy, recognised in political theory as delegated repression, allows power to remain formally invisible while its coercive effects become increasingly visible and normalized.

In this context, state silence is not neutrality but a political stance. When teachers are encircled, humiliated, threatened, or pressured to resign, and authorities fail to intervene, that silence functions as tacit endorsement. A government committed to protecting universities would respond with transparent investigations, institutional accountability, and firm rejection of mob coercion. Instead, we see administrative inertia and, often, surrender to street pressures. This is not accidental; it is part of a governing strategy that relies on ambiguity to avoid responsibility.

A key question arises: why are academics the primary targets? Why not journalists, professionals, or other civil groups? The answer lies in the nature of academic labour. Universities produce knowledge, and knowledge can resist, disrupt, and reinterpret power. As Foucault reminds us, power and knowledge are intertwined; to control one, the other must be constrained. When teachers lose the freedom to question society, history, religion, morality, or the state, it becomes far easier for political actors to impose singular narratives. The current attacks are therefore not merely personal assaults but epistemic assaults, attempts to erode society’s capacity to think critically.

Authoritarian and semi-authoritarian regimes have historically found universities threatening because they interrogate power and unsettle dominant narratives. From Nazi Germany to Latin American dictatorships and military-era Turkey, universities have been among the earliest targets of repression. Bangladesh is now witnessing a localized version of this pattern. Censorship is repackaged as “mob reaction,” and state complicity is reframed as “maintaining order.” The interim government, by failing to intervene, has effectively assumed the role of manager rather than protector.

This violence also produces a dangerous moral inversion. Perpetrators no longer see themselves as aggressors but as defenders of justice. Verbal abuse, public shaming, and physical intimidation are recast as “appropriate punishment.” As Hannah Arendt warned, the banality of evil emerges when harmful acts become morally normalized. When the state refuses to challenge these distortions, it becomes complicit in them.

The consequences for academic freedom are profound. Formally, teachers remain “free,” but in practice they know which topics are risky, which theories may provoke outrage, and which classroom discussions could be recorded or weaponized. Self‑censorship becomes the most effective tool of control, hollowing out the intellectual life of the university from within.

Students, ultimately, bear the greatest cost. Those who learn to exercise power through intimidation today may graduate into a system where critical thinking is discouraged, curricula are diluted, and degrees lose international standing. Short-term empowerment is purchased at the price of long-term intellectual and institutional decline.

In this reality, the interim government cannot evade responsibility. Protecting teachers and safeguarding academic freedom are non-negotiable duties of the state. Failure to act is not mere administrative weakness; it reflects a governing philosophy that prioritizes control over knowledge and conformity over critical thought.

Where teachers are unsafe, truth is unsafe, and where truth is unsafe, the future becomes unsafe as well.