Bangladesh stands at a defining constitutional moment. On February 12, as an estimated 127 million citizens cast their votes in a parliamentary election, they will also be asked to decide—through a nationwide referendum—whether to approve the so-called July Charter. What appears, at first glance, to be a democratic exercise may, in fact, represent something far more consequential: a fundamental challenge to the constitutional order itself.

The referendum presents voters with a single, binary choice—yes or no—on 84 proposed reforms, at least 47 of which would directly amend the Constitution. In practical terms, this would require the electorate to approve sweeping constitutional changes in one stroke, effectively endorsing a structural reconfiguration of the state.

A Legal Grey Zone

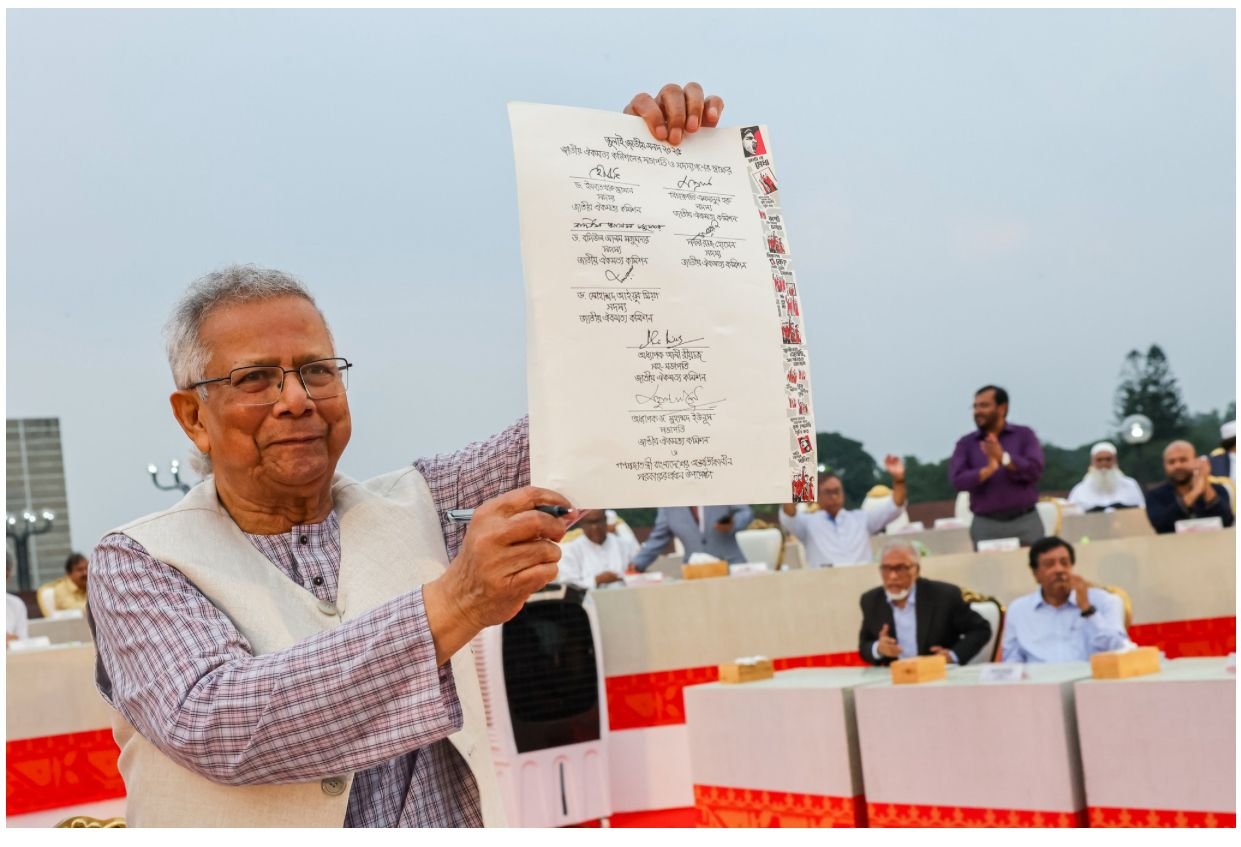

The constitutional legitimacy of this referendum remains deeply contested. The interim government led by Professor Muhammad Yunus, installed following the removal of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina on August 5, 2024, has defended the process by invoking the doctrine of popular sovereignty and the concept of primary constituent power. The administration argues that since the people are the ultimate source of authority, they may alter even entrenched constitutional provisions through a direct plebiscite.

While such reasoning carries democratic appeal, it also produces a profound legal paradox. If the referendum operates outside the existing constitutional framework, it cannot be considered a lawful amendment. Instead, it becomes an act of constitutional refounding—the creation of a new legal order without formally abandoning the old one.

This contradiction is stark. The interim administration claims legitimacy from the Constitution, governs under its authority, and is conducting elections pursuant to it—yet simultaneously seeks to override that very constitutional structure. An authority cannot draw legitimacy from a document while undermining its supremacy.

Popular Sovereignty Has Limits

Bangladesh’s Constitution firmly anchors popular sovereignty, but it does so within defined legal boundaries. Article 7(1) declares that all power belongs to the people, but explicitly states that such power must be exercised “only under, and by the authority of, this Constitution.” This clause is critical: it rejects the notion that the people may exercise binding sovereign power at any time, in any manner, simply through mass voting.

Constitutional democracies do not reject popular will; they organize it. Part X of the Constitution establishes the exclusive procedure for constitutional amendment, ensuring continuity, predictability, and legal stability. Any attempt to exercise constituent power outside this framework threatens constitutional coherence.

Article 7(2) reinforces this structure by nullifying any law or action inconsistent with the Constitution. A referendum implemented through executive ordinance or statute—if it contradicts the amendment process outlined in Part X or bypasses entrenched provisions—would collide directly with this supremacy clause.

Consent Must Be Informed

Beyond legality, constitutional legitimacy requires informed consent. Democratic participation is meaningful only when voters clearly understand what they are being asked to approve or reject. Yet widespread public confusion surrounds the July Charter and its long-term implications.

This problem is compounded by the referendum’s design. Voters are forced to accept or reject dozens of unrelated reforms as a single package—compelling them to endorse unwanted changes in order to secure desired ones, or to sacrifice beneficial reforms to block objectionable provisions.

Concerns about procedural fairness have also been raised. The Election Commission has clarified that active campaigning by the interim government would breach its duty of neutrality. Despite this, Professor Yunus publicly urged citizens to vote “yes,” framing the referendum as a pathway to liberation from discrimination and oppression, without clearly explaining the mechanisms involved. A subsequent rule even allowed government officials to campaign for approval—further eroding the deliberative integrity of the process.

Article 7B: The Constitutional Firewall

The most formidable legal obstacle to the referendum lies in Article 7B, introduced through the Fifteenth Amendment in 2011. This provision explicitly declares certain constitutional elements unamendable, stating that they may not be altered “by insertion, modification, substitution, repeal, or by any other means.”

This language is deliberate. It is designed to prevent circumvention of constitutional entrenchment through alternative mechanisms, including referendums.

Bangladesh’s codification of the basic structure doctrine is unusual in global constitutional practice. Unlike India—where the doctrine is judicially derived—Bangladesh embeds it directly in the constitutional text. Article 7B protects the Preamble, Parts I, II, and III of the Constitution, and other foundational principles forming the basic structure.

Although portions of the Fifteenth Amendment have been questioned by the Supreme Court, Article 7B remains legally operative until formally altered through constitutionally prescribed means.

Direct Conflicts with the July Charter

Several provisions of the July Charter appear to clash directly with Article 7B’s protected domains:

- Binding reform mandates: The Charter requires the next elected parliament to implement 30 reforms deemed mandatory, limiting parliamentary autonomy under Article 65 and undermining representative democracy.

- Bicameral legislature proposal: The introduction of a 100-member upper house elected through proportional representation would fundamentally alter the structure of Parliament, implicating core principles of democratic governance and separation of powers.

- Restoration of the caretaker government system: Reversing its abolition affects executive authority and governance arrangements protected as part of the constitutional basic structure.

A Dangerous Precedent

The implications extend far beyond a single referendum. Approving the July Charter through a binding plebiscite risks normalizing constitutional disregard during political crises. Once constitutional constraints are bypassed in the name of expediency, future governments may do the same—pushing the country into cycles of legal uncertainty and institutional instability.

In a constitutional democracy, majority rule does not eclipse constitutional supremacy. When plebiscites override entrenched legal safeguards, the Constitution ceases to function as the supreme law, and popular rule risks becoming arbitrary.

Defending constitutional integrity is not resistance to reform. It is an insistence that reform occur through the Constitution, not against it.

Attribution & Credit

This article is an original rewrite based on ideas and arguments presented in:

Arafat Hosen Khan & Sangita F. Gazi, “Plebiscite or Refounding? The Constitutional Limits of the Referendum in Bangladesh”, The Diplomat, February 6, 2026.

All analytical credit for the underlying legal arguments belongs to the original authors.