Expert Comments

Bangladesh–US Trade Agreement in Focus Unequal, Rushed and Risky

Prof Selim Raihan warns the deal raises serious questions about Bangladesh’s economic sovereignty and geopolitical balanceA trade agreement signed between Bangladesh and the United States on February 9 — just days before a national election — has triggered sharp criticism from economists and policy observers.The Agreement on Reciprocal Trade, concluded by the interim government in the final days of its tenure, offers only a marginal reduction in US tariffs. Yet it binds Bangladesh to a sweeping framework covering defence, energy, trade, labour standards and digital governance.“The agreement could reshape Bangladesh’s economic autonomy, geopolitical balance and long-term development path,” said Professor Selim Raihan, Executive Director of the South Asian Network on Economic Modeling (SANEM), in an extended interview.Raihan described the deal as “highly unequal”, “rushed” and “potentially damaging” to Bangladesh’s strategic independence. A Question of TimingRaihan’s first concern centres on timing. The agreement was finalised by an interim administration just days before the election — a move he believes sets a troubling precedent.“I do not understand why our interim government rushed to sign this agreement just before the election,” he said. “This should have been left to the newly elected government. Waiting one or two months would not have created major problems.”He contrasted Bangladesh’s approach with India’s slower and more cautious negotiations with Washington.“I was informed that India and the United States have not yet signed their trade agreement. If a country like India has not finalised such a deal, why were we in such a hurry?” he asked.Raihan argued that an agreement of this magnitude required parliamentary scrutiny and broad consultation with exporters, business leaders and trade experts.“Stakeholders were not properly consulted,” he said. “The process is deeply concerning.” Imbalance in ObligationsOne of Raihan’s strongest criticisms concerns the imbalance of commitments.“In the 32-page document, the phrase ‘Bangladesh shall’ appears 158 times, while ‘the United States shall’ appears only nine times,” he noted. “This shows that most obligations fall on Bangladesh.”Under the agreement, Bangladesh will open its market to approximately 6,700 US products — including chemicals, medical devices, machinery, ICT equipment, motor vehicles, beef and poultry. In contrast, the US grants duty-free or preferential access to around 2,500 Bangladeshi items.In return, Washington reduces its reciprocal tariff on Bangladeshi exports from 20 percent to 19 percent.“For a trade agreement between the most powerful economy in the world and one of the weakest economies among least developed countries, this is highly unequal,” Raihan said.“The weaker country is offering more, while the superpower is offering less. Bangladesh is effectively granting special and differential treatment to the United States.” Strategic and Sovereignty ConcernsBeyond trade, Raihan raised concerns about provisions that may constrain Bangladesh’s policy autonomy.The agreement requires Bangladesh to endeavour to increase purchases of US military equipment and restrict procurement from certain countries — language widely interpreted as targeting China. It also allows Washington to terminate the deal if Bangladesh signs trade agreements with countries classified as non-market economies.“In areas such as defence procurement and trade relations with other countries, Bangladesh may effectively require US endorsement,” Raihan said. “This raises concerns about sovereign decision-making.”The deal also emphasises “economic and national security alignment,” which Raihan described as potentially intrusive.“This is not just about trade. It is geopolitics,” he said. “Bangladesh is vulnerable in global geopolitical competition, and we must be careful.” Risk to Non-Aligned StatusRaihan warned that the agreement could gradually shift Bangladesh away from its long-standing non-aligned foreign policy stance.One provision requires Bangladesh to adopt complementary restrictive measures if the US imposes border or trade actions on national security grounds. Critics argue this could effectively bind Dhaka to US sanctions regimes.“If the United States bans products from certain countries, Bangladesh may be expected to support that,” Raihan said. “This could alter our non-aligned position.”Managing relations with China — Bangladesh’s largest import partner — would become particularly complex.“China is our largest import source, yet the US has ongoing trade conflicts with China,” he said. “If Bangladesh is pressured to reduce imports from China, it will be extremely difficult. We need balanced relations with everyone — China, India, the US and others.” ‘Zero Tariff’ ConfusionRaihan also criticised what he called misleading communication about tariff benefits.“When officials spoke of ‘zero tariff’ for products using US cotton, it actually refers to zero reciprocal tariff — not total tariff removal,” he explained. “The original Most-Favoured-Nation (MFN) tariff remains.”Many exporters reportedly misunderstood the provision as full tariff elimination. Managed Trade and Financial PressureAnother major concern is the shift toward what Raihan describes as “managed trade”.Bangladesh has committed to purchasing approximately $15 billion worth of US liquefied natural gas over 15 years, alongside increased imports of aircraft and agricultural goods.This includes plans for Biman Bangladesh Airlines to purchase 14 Boeing aircraft and at least $3.5 billion in US agricultural products such as wheat, soybeans and cotton.“The idea is to reduce the bilateral trade deficit,” Raihan said. “But this means importing more from the United States regardless of competitive pricing.”He warned that Bangladesh could be compelled to buy higher-cost goods even when cheaper alternatives exist.“This will put additional pressure on foreign exchange reserves,” he said. “How will we finance aircraft purchases and energy imports? There is a risk of increased reliance on foreign loans.” Labour and Regulatory ChangesThe agreement also requires amendments to labour laws, including expanded union rights and bringing export processing zones under national labour standards within two years.“Labour is a very sensitive issue in Bangladesh,” Raihan said. “If these provisions create uncertainty among investors, particularly in the garment sector, it could create serious problems.”He further expressed concern about clauses requiring Bangladesh to recognise US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approvals for pharmaceuticals and medical devices — potentially weakening domestic regulatory authority. Limited PositivesDespite his criticisms, Raihan acknowledged some potential benefits.“There is a positive area in addressing non-tariff barriers,” he said. “But reforms should apply universally, not just for one country.”Reducing bureaucratic inefficiencies could benefit both domestic and foreign businesses, he added. A Dilemma for the Next GovernmentRaihan believes the agreement will present a significant challenge for the incoming administration.“The next government will already face domestic political and economic pressures,” he said. “They may seek a review rather than outright cancellation.”Cancelling the deal could harm Bangladesh’s credibility.“Signing and then cancelling sends a negative signal to trading partners,” he noted.Yet moving forward would lock Bangladesh into long-term financial and strategic commitments.“The pressure will remain — financial, strategic and geopolitical,” Raihan said.“We need everyone — China, India, the United States and others. Maintaining that balance is crucial for Bangladesh’s future.” Selim Raihan12 February 2026, 00:00 AMThe Daily Start

.jpeg)

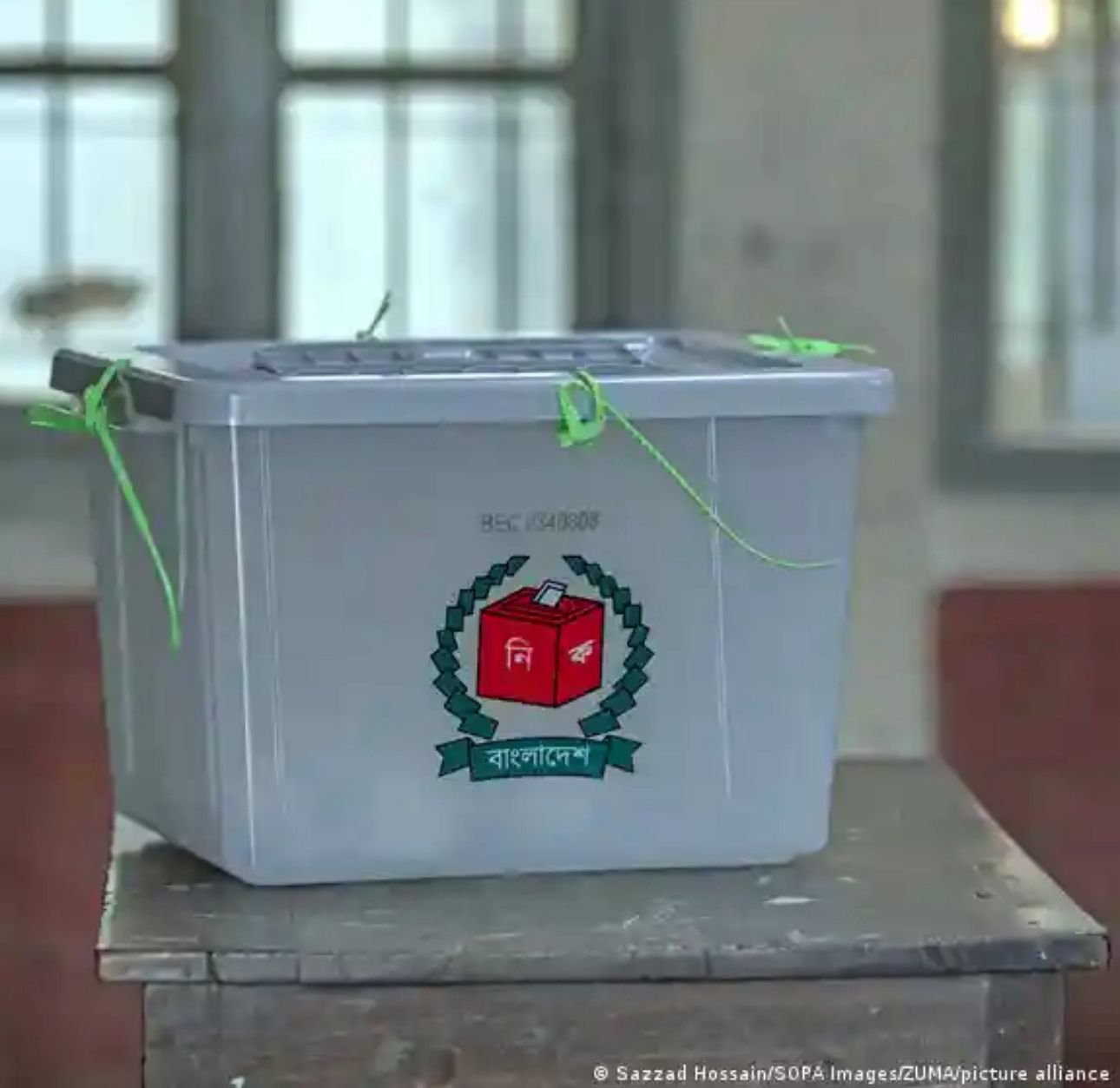

Politicians must be open to accepting electoral defeats

Three features distinguish the upcoming national election in ways rarely seen before: the resurgence of Jamaat-e-Islami, the rise of Tarique Rahman as a central figure in contemporary politics, and—unthinkable until August 2024—the sidelining of the Awami League from the electoral contest.Since its role during the Liberation War—when it opposed the birth of Bangladesh, aided the Pakistan Army in committing genocide, and collaborated with al-Badr and al-Shams in the killing of intellectuals—Jamaat-e-Islami has remained one of the most controversial actors in our political history. Its refusal to apologise explicitly for its role in 1971 or seek forgiveness from the people of Bangladesh has long rendered its political acceptability deeply questionable.Its current position, articulated by party chief Dr Shafiqur Rahman—that “if we have committed any mistake since 1947 till date, we apologise for it”—is telling. By avoiding any direct reference to 1971, Jamaat continues to evade accountability for opposing the independence struggle and acting against the aspirations of freedom-loving people. This refusal remains among the most tragic aspects of our political journey.Yet despite this legacy, Jamaat is today a formidable presence in the upcoming election. Opinion polls suggest it may emerge as the second-largest party in the next parliament. How did a party burdened with such a past manage this resurgence?The most significant factor is Jamaat’s strategic mobilisation of the growing consciousness of Muslim identity among the majority of Bangladeshis, positioning itself as its most authentic representative. This was made possible by the failure of the two centrist parties—the Awami League in particular, and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party to a lesser extent—to firmly entrench a durable tradition of nationalistic and secular politics in the public imagination.Both parties governed the country since 1991, yet their performance increasingly alienated voters. The Awami League’s corrupt, exploitative, and oppressive rule over more than fifteen years—ending in August 2024—proved especially damaging. Ironically, a party whose legitimacy was rooted in its role in 1971 squandered that moral capital, opening space for Jamaat’s political rehabilitation.Jamaat’s ideological consistency, organisational discipline, and the dedication of its grassroots activists have further strengthened its position. Its long-term infiltration of Chhatra League structures, sometimes even assuming second-tier leadership roles, demonstrates strategic patience and organisational skill. Shibir’s recent victories in student union elections at five public universities further underline this success. Reports also suggest that Jamaat’s female grassroots workers have been particularly effective in door-to-door campaigning.In this context, Jamaat’s electoral ally, the National Citizen Party (NCP), also warrants attention. Born out of the July uprising, NCP entered electoral politics amid high expectations. Its decision to align with the Jamaat-led bloc may prove consequential—both in the immediate election and for its long-term political identity.The second defining feature of this election is the rise of Tarique Rahman. Though long regarded as the heir apparent, the scale and speed of his ascent have been striking. Operating from London for years while his mother remained incarcerated, he managed to keep the BNP not only alive but disciplined and cohesive—no small feat under relentless repression.Tarique Rahman’s direct communication with grassroots leaders through mobile and internet platforms fostered loyalty and pride among younger BNP activists. Repeated attempts by the Awami League to fracture the party or co-opt senior leaders were thwarted by his persuasive engagement. Fifteen years is a long time in Bangladeshi politics, and the BNP’s survival through that period is a testament to his organisational capacity.Many felt he delayed his return to Bangladesh after the fall of the Awami League government. Yet when he did return, the impact was immediate. His presence electrified party workers, energised supporters, and restored confidence. Massive public turnouts and warm receptions at his appearances have made him a central force in the electoral landscape.Thus far, he has conducted himself with restraint and maturity. His speeches have been measured, forward-looking, and policy-oriented—standing in contrast to the rhetoric-heavy approach of many others. Whether he has translated this momentum into effective nationwide campaign organisation will become clear only after the polls. But he has convincingly stepped into the political space once occupied by his late mother, whose janaza remains a powerful reminder of the affection and respect she commanded.The third and perhaps most consequential feature of this election is the effective exclusion of the Awami League. The party has not been formally banned, but its political activities have been. How could a party so integral to the birth and history of Bangladesh become so vulnerable as to be sidelined from a national election?The reasons are many—extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances—but the decisive factor lies in the brutal street violence during the final weeks of its rule. One incident encapsulates this collapse of legitimacy: the killing of Abu Sayed, an unarmed university student standing alone, posing no threat, shot dead by police. That single act symbolised the moral and political implosion of the regime.The government’s subsequent conduct—tampering with autopsy reports, attempting justification instead of accountability, and continuing the killing of demonstrators—sealed its fate. The loss was total: public trust, credibility, and legitimacy. The ban on AL’s activities flowed directly from this record.Where Awami League voters will shift their support on February 12 may well determine the election’s outcome.An additional feature worth noting is the eclipse of the Jatiya Party, once dominant under General HM Ershad and consistently the third-largest force in parliament since 1990. Its marginalisation reflects the profound restructuring underway in Bangladesh’s political order.Elections are always pivotal in a democracy. This year, however, they carry exceptional weight. Bangladesh urgently needs stability, predictability, an end to mobocracy, renewed investment, and restored public safety. These can only begin with an elected parliament, an accountable government, capable policymakers, and a clear national vision.We conclude with a warning drawn from experience. While we are enthusiastic about elections, we have historically been unwilling to accept defeat. Losing candidates accept results more readily than losing parties—those that fail to form the government often delegitimise the process itself. We have seen this repeatedly, even under caretaker governments.As we once observed, the mindset has been: an election is free and fair if we win, but rigged if we lose. This attitude must end.It is our sincere hope that all political actors accept the outcome with grace and dignity. If there are fact-based grounds for challenge, pursue them through the mechanisms laid down by the Election Commission. Do not resort to chaos or disruption. The nation must move forward—peacefully and urgently.Here’s to a free, fair, and peaceful election.Mahfuz Anam is the editor and publisher of The Daily Star.Views expressed are the author’s own.

Exclusive: ‘Bangladesh Must Return to the Rule of Law’ — Lord Carlile Warns from House of Lords

Senior British lawmaker Lord Alex Carlile has issued a stark warning about Bangladesh’s political and judicial direction, calling for urgent restoration of the rule of law, free and fair elections, and political plurality, during an exclusive interview with Politika News at the House of Lords.Speaking on the sidelines of a parliamentary seminar on Bangladesh, Lord Carlile said the discussion was essential for British parliamentarians, many of whom maintain long-standing support for Bangladesh and its democratic aspirations.“I think it’s very important for British parliamentarians to discuss what is going on in Bangladesh. Many of us here feel a great deal of support for Bangladesh and particularly for the notion of free and fair elections and Bangladesh making its way back into the friendliness of nations — the community of nations, as we call it.”However, he stressed that reintegration into the international community must be achieved through lawful means.“It has to be done properly, and we’re very concerned about the nature of the trials that are taking place at the moment, and about the facilities being given to defendants in these trials. However guilty some of them may be, they’re entitled to fair trials.”Lord Carlile expressed hope that Bangladesh would embark on a process of reconciliation and truth, allowing all legitimate political parties to participate in elections.“We hope that a process will be started which is one of reconciliation and truth, and that when the elections take place, all proper political parties can participate, and the world at large will look upon Bangladesh as a nation that is welcomed back into the family of nations — which it is not at the moment. At the moment, it’s regarded as an outlier.”Responding to a question about reports that Sheikh Hasina had been given a death sentence by Bangladesh’s International Crimes Tribunal, Lord Carlile was unequivocal in his legal assessment.“Well, I’m a lawyer, right? I’m a British King’s Counsel, and my reaction is that the process of the trial was not a proper, fair trial. She was not entitled to choose her own counsel.”He cited a recent incident in the same court as deeply troubling.“Indeed, in another case yesterday in the same court, there was a shocking exchange between prosecuting and defence counsel in which prosecuting counsel, according to reports — if they’re correct — threatened defence counsel that she might be put on trial. That is not compliant with the rule of law.”Lord Carlile said Britain’s own parliamentary system, grounded in legal safeguards, has a responsibility to support Bangladesh’s return to democratic norms.“So we are here in the UK Parliament — a Parliament that’s subject to the rule of law — to help Bangladesh return to the rule of law, have free and fair elections, and plurality of political parties in the future, so we don’t swing from one dynasty to the other every few years.”Asked whether elections under the interim government could be genuinely free and fair, he said interim leader Muhammad Yunus appears committed to that goal, though obstacles remain.“At the moment, I believe that Muhammad Yunus, the interim leader, wishes to have free and fair elections. I’m not sure that everyone in the interim administration agrees with him, and I hope that he will have his way, and that we will see free and fair elections. Otherwise, we’ll be back where we are in three or four years’ time.”He called for a national reset.“This should now be a resettlement, a calming down, and reconciliation, so that those who are fit to stand for election — and there will be some who will have to be disqualified — those who are fit to stand for election are enabled to do so, whichever political parties they come from.”On whether elections should proceed under the caretaker administration, Lord Carlile said conditional support was essential.“I think the election should be under the caretaker government, but they have to give guarantees of freedom and fairness, and I think there should be international observers to ensure that freedom and fairness. Otherwise, it will not be credible.”Addressing the role of student protesters who helped bring down the Awami League government, he said they had achieved their core objective.“Student protesters achieved what I thought they wanted to do, which is to bring an end to the Awami League government, which in my view committed many gross errors and worse — but to have free and fair elections.”He added that political exclusion would undermine that achievement.“Now, if the Awami League is still a political party and has people who have not been involved in killings and violence, who wish to stand as Awami League candidates in an election, then the circumstances should be created in which they can do so.”Lord Carlile said he would prefer a delay in elections if it allowed time for reconciliation.“I would be much happier if the election was delayed somewhat longer so that there could be a truth and reconciliation commission set up to sort out who can stand in the elections, and then they will be free and fair, with foreign observers involved.”On proposals to hold elections alongside a referendum, he expressed concern that the current process is failing.“I think that there should be a reset of the situation now because it’s not working. The interim leader Muhammad Yunus wishes to have free and fair elections, but he’s being prevented from doing so.”He concluded by urging student leaders to reconsider their role.“The students and their leaders now step back from claiming political leadership, unless they’re prepared to resume full democracy.” Source:Exclusive interview with Lord Alex CarlileMember of the House of Lords, United KingdomHouse of Lords, London | 25 November 2025

Bangladesh’s Moment of Truth: Reform, Justice, or Another Lost Decade

Bangladesh’s political future, economic direction, and international standing now hinge on whether the country can translate promises of reform into genuine rule of law, warned Lord Alex Carlile in a detailed and candid statement at the House of Lords on 25 November 2025.Opening a meeting whose working title he described as “not snappy,” Lord Carlile suggested it could be more accurately summarised as “Bangladesh: Revive and Reform.” He stressed from the outset that the purpose of the discussion was not to attack Bangladesh, but to allow frank, even uncomfortable, criticism intended to be constructive.Lord Carlile told the gathering that his engagement with Bangladesh spans more than two decades, beginning with his first visit in 2005. His involvement deepened during his tenure as the United Kingdom’s Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation, when he was asked by the British government to examine how terrorism was defined in UK law. As part of that work, he commissioned extensive global research into counterterrorism legislation, identifying what appeared on paper to be some of the strongest legal systems in the world.What he discovered, he said, was a recurring and dangerous gap between law and practice. Countries with exemplary “black letter” laws often applied them in the worst possible ways. He illustrated this with an experience in Pakistan, where he addressed a room full of judges. Every judge confirmed they had tried terrorism cases, yet not a single one had ever secured a conviction. The lesson, Lord Carlile argued, was clear: the quality of a law is meaningless unless it is applied properly and independently.It was against this backdrop that he later encountered Bangladesh’s legal and political environment. He said he met many significant figures and saw a country with immense potential — a large population, a functioning university system, strong historical ties with the United Kingdom, and a capable legal profession, much of it trained in Britain’s Inns of Court. Despite political complexities, he said he initially felt optimistic about Bangladesh’s future.That optimism faded over time. Reflecting on the past 20 years, Lord Carlile said Bangladesh had effectively been governed by two administrations, neither of which, in his view, would “win the Nobel Prize for good government.” Elections were routinely unfair, courts failed to operate according to international rule-of-law standards, and undocumented killings of a terrorist nature were carried out by state actors. Politics, he said, became dominated by vengeance between two dynastic parties, creating an atmosphere that left him deeply pessimistic about the country’s trajectory. Economic progress during this period, he added, was mixed, while political progress remained limited.The student-led protests that eventually brought down the last government marked a turning point. Lord Carlile said he felt renewed optimism — not because of how the government fell, but because it represented a genuine, de facto change of power. He described interim leader Muhammad Yunus as a good choice, expressing his belief that Yunus was genuinely motivated to establish a government rooted in the rule of law. If achieved, Lord Carlile argued, such governance could trigger an economic surge capable of elevating Bangladesh into the ranks of Asia’s tiger economies.He pointed to global manufacturing trends to illustrate what Bangladesh could become. Cars are now being built in China, he said, but there is no reason they should not be built in Bangladesh. Luxury clothing for global designer labels is manufactured in China, Romania, Albania, and other emerging economies — yet Bangladesh has not fully captured that opportunity, despite being well placed to do so.Despite recognising the presence of well-intentioned politicians who share Yunus’s reformist aims, Lord Carlile warned that serious problems persist. Since the fall of the Awami League government, he said, there have been reports of extrajudicial killings. Prospective elections, if held as planned, risk being neither free nor fair. Most concerning, he argued, is the exclusion of a major political party from the political process. Regardless of that party’s past actions, banning it as an organisation — rather than disqualifying specific individuals through due process — is, in his view, a grave mistake.Lord Carlile said Bangladesh missed a critical opportunity to establish a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, drawing comparisons with Northern Ireland, South Africa, and Rwanda. Such a mechanism, he argued, could have disqualified individuals unfit for public office while allowing legitimate candidates to contest elections. Without it, Bangladesh risks swinging back to the very political conditions it is trying to escape.He expressed deep concern over the tribunal proceedings against former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina. Even if she were guilty of every allegation against her, he said, she remains entitled to a fair trial. Denying her the right to appoint counsel, restricting her ability to appear, or failing to disclose evidence properly undermines justice itself. Lord Carlile warned that the manner in which this process is unfolding is dangerous not only for the accused, but for Bangladesh’s legal future.Bangladesh’s international reputation, he added, is also at stake. Though a member of the Commonwealth, the country is increasingly viewed as an outlier — even a renegade — because of its failure to adhere to rule-of-law norms. Full re-engagement with the Commonwealth, he said, could provide vital support and legitimacy, emphasising that the organisation is no longer UK-centric but a collective of nations committed to mutual assistance.If elections were conducted with international consultation or supervision, and reconciliation mechanisms were put in place, Lord Carlile said there would be a real chance of breaking Bangladesh’s dynastic political cycle. He was clear that both the Awami League and the BNP should evolve into genuine political parties rather than vehicles of personal power.The stakes, he warned, are not merely political but economic. Governments that silence opposition and suppress dissent inevitably weaken themselves. Political exclusion drives instability, deters investment, and stalls growth. Economic stagnation deepens poverty, which in turn fuels further dissent — a spiral that can lead to national crisis.Lord Carlile concluded by urging participants to take the message of the meeting back to their contacts in Dhaka. He warned that current actions fall short of the ambitions that led Muhammad Yunus to be called upon to save the country. “At the moment,” he said, “he looks like a tragedy, not a saviour — but he can still be a saviour.” Source:Lord Alex CarlileMember of the House of Lords, United KingdomStatement at the House of Lords, 25 November 2025

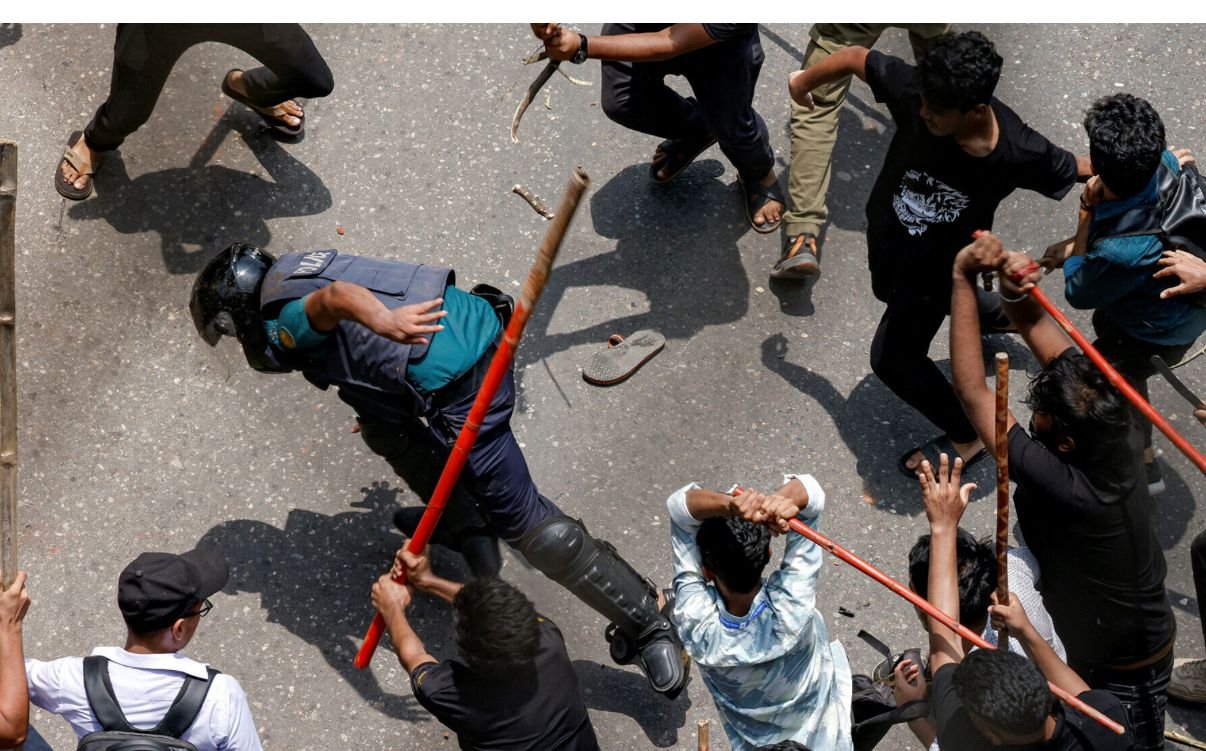

Election legitimacy and the absence of the Awami League

Apart from Bangladeshis’ understandable preoccupation with who will win the upcoming election—BNP or Jamaat-e-Islami—two further questions dominate discussion around the February 12 vote.First, will there be manipulation of votes, as has occurred to varying degrees in every election in Bangladesh, or will the result genuinely reflect the will of the electorate? Second, a question few are willing to raise openly within the country but which is discussed more freely abroad: can an election be considered fair and legitimate in the absence of the Awami League?This article is primarily concerned with the second question, though a brief comment on electoral manipulation is warranted. There is little doubt that nefarious actors exist—at both local and national levels—within all major party blocs, as well as within the administration and the security forces. If given the opportunity, such actors may seek to tilt the electoral process in favour of one side or another.While the government insists this will be the cleanest election in the country’s history, it remains uncertain whether sufficient safeguards and scrutiny exist—within the Election Commission, among observers, or in the media—to prevent rigging. Ultimately, this can only be judged on polling day itself and through subsequent reporting. That said, it appears likely that any manipulation, should it occur, would be relatively limited in scope.Even assuming there is no rigging, or no substantive rigging, the more fundamental question remains: can an election be described as “fair” or legitimate in the absence of the Awami League?In principle, a genuinely fair election should allow the participation of all political parties. Throughout Bangladesh’s history, the Awami League has consistently been either the most popular or the second most popular party. Even now, were it permitted to contest the election, the party would almost certainly win a number of seats—though not enough to secure overall victory. Its participation would nonetheless have a decisive impact on the outcome, shaping which of the remaining parties emerged on top and potentially allowing the Awami League to hold the balance of power.In short, an election that included the Awami League would look markedly different from the one scheduled to take place in just over a week’s time. This reasoning underpins the party’s claim that its exclusion is wholly unjustified and that any resulting government would lack legitimacy.In advancing this argument, however, the Awami League largely ignores the context in which the decision to exclude it was taken. That context is the party’s role in supporting—and in key respects facilitating—the government’s response to the July 2024 protests. As documented by the International Truth and Justice Project, detailed mapping of the violence confirms that more than 800 individuals were killed by law enforcement authorities during this period.This is not a peripheral matter. It is the central reason the party now finds itself outside the electoral process. Yet this context is not only downplayed by the Awami League itself; it is also frequently minimised or omitted by journalists and commentators sympathetic to the party’s current predicament.The key question, then, is whether this context is sufficient to justify the Awami League’s exclusion.One way to approach this is through a thought experiment: to consider how similar events would be viewed, and what political consequences would likely follow, if they occurred in another democratic country—however implausible that may seem.Imagine, for example, that something similar happened in Britain.The prime minister, Keir Starmer, orders the police and security forces to use lethal force against protesters. Over several weeks, hundreds are killed and thousands seriously injured. Almost all Labour ministers, MPs, and senior party figures either publicly support the policy, remain silent, or conspicuously fail to criticise it. Starmer and other senior figures actively encourage local Labour constituency organisations to mobilise in support of law enforcement. In some areas, Labour activists take to the streets backing the security forces; some even carry firearms and shoot at protesters.When the UK army refuses to fire on civilians, Starmer and a significant portion of the Labour leadership flee the country, taking refuge in France. The United Nations dispatches a fact-finding mission, which later concludes that, in support of the government, “violent elements associated with” the Labour Party systematically engaged in serious human rights violations, including “hundreds of extrajudicial killings.”Yet over the following year and a half, neither Starmer nor any senior Labour figure—whether abroad or at home—acknowledges the party’s or the government’s culpability. Leaked recordings even suggest that Starmer, who remains Labour leader, is encouraging party activists inside the UK to continue using violence.If such events were to occur in Britain—or in any other liberal democratic country—it is extremely difficult to imagine that the political establishment would allow the Labour Party to contest the next general election. The party would almost certainly be regarded as having crossed fundamental democratic red lines and would be barred from participation. Only after a clear break in leadership and a credible process of accountability might re-entry into electoral politics be conceivable.If such conduct would justify excluding a major party in the UK, it is difficult to argue that Bangladesh’s authorities are acting unreasonably in reaching a similar conclusion with respect to the Awami League. There are circumstances in which the exclusion of a major political party does not undermine an election’s legitimacy but instead represents a response to conduct that has placed that party, at least temporarily, outside the bounds of democratic acceptability. The Awami League’s response to the July uprising constitutes such a circumstance.It is true that Bangladesh has no shortage of highly partisan opponents of the Awami League who, for their own political purposes, exaggerate the extent to which the entire party—at national, district, and local levels—was complicit in the July killings. This overreach is reflected in the criminalisation of party activities and in the arrest and imprisonment of hundreds, perhaps thousands, of party members without supporting evidence.These excesses are real, troubling, and must be acknowledged. But one need not accept exaggerated claims or endorse abusive legal measures to recognise the force of the narrower argument: that the Awami League, in its current form, should not be permitted to contest this election. Even allowing for exaggeration and abuse by its opponents, the core justification for the party’s exclusion remains intact. On that basis, an election held without the Awami League cannot simply be dismissed as illegitimate.That said, the party’s exclusion is not cost-free. It significantly distorts the electoral landscape. A substantial segment of the electorate—long-standing Awami League supporters—is effectively disenfranchised, forced either to vote for parties they do not support or to abstain altogether. This reality cannot be ignored. Even if the party’s exclusion is justified, its complete absence from the political arena is not healthy for Bangladesh’s democratic development.For this reason, one need not support the Awami League to argue that serious efforts should be made in the coming years to enable the emergence of a renewed party: one grounded in its historic commitments to 1971, secularism, and social liberalism, but led by new leadership that has clearly and credibly broken with those directly responsible for the July killings. A return to normal democratic competition will require the party to undertake a genuine process of accountability, reckoning, and reform—and it must be both encouraged and pressured to do so.If such a process is to be possible, the next elected government will have a crucial role to play. It must move away from some of the most damaging practices of the interim period, including the blanket banning of Awami League activities and the use of mass arrests and prolonged detention without evidence. Only prosecutions supported by credible and sufficient evidence should proceed; all others should be released. Those within the party who seek reform cannot begin that difficult work while a boot remains on the party’s neck. David BergmanX (formerly Twitter): @TheDavidBergmanThe views expressed in this article are the author’s own.

Bangladesh election: What’s at stake for India, China, and Pakistan?

As Bangladesh prepares to hold its first election since the overthrow of former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina and her Awami League government in 2024, neighbouring India, Pakistan, and China are watching closely.The country is currently governed by an interim administration led by Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus. The two principal parties competing for power in this month’s polls are the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and Jamaat-e-Islami (JIB), both of which began campaigning in late January.The Awami League—historically one of Bangladesh’s dominant political forces and a close ally of India—has been barred from contesting the election due to its role in the violent crackdown on student-led protests in 2024. Former prime minister Hasina, now 78 and living in exile in India, was found guilty of authorising the use of lethal force against protesters, during which at least 1,400 people were killed.In November last year, Bangladesh’s International Crimes Tribunal tried Hasina in absentia and sentenced her to death. India has so far refused to extradite her.Hasina has denounced the upcoming election, telling the Associated Press last month that “a government born of exclusion cannot unite a divided nation.”Since her ousting, analysts say Bangladesh’s geopolitical posture has undergone a significant shift.“Bilateral relations with India have reached a historic low, while ties with Pakistan have warmed considerably. At the same time, strategic engagement with China has deepened,” said Khandakar Tahmid Rejwan, a lecturer in global studies and governance at Independent University, Bangladesh.He noted that Hasina’s 15-year rule was defined by three key foreign policy pillars: close and comprehensive relations with India; diplomatic distance from Pakistan; and a carefully calibrated partnership with China focused on defence, trade, and infrastructure.“That predictable alignment has now been reversed with respect to India and Pakistan, and recalibrated in relation to China,” Rejwan said.So how do India, Pakistan, and China view the upcoming election—and does the outcome matter to them? India-Bangladesh relationsUntil Hasina’s fall, India regarded Bangladesh as a critical strategic partner in South Asia. India is Bangladesh’s largest Asian trading partner, exporting goods worth $11.1bn between April 2023 and March 2024, while importing $1.8bn worth of Bangladeshi products.Since Hasina fled to India, however, relations have deteriorated sharply. Both countries have imposed trade restrictions amid rising political tensions.Although India supported Bangladesh’s independence from Pakistan in 1971, bilateral relations have fluctuated over the decades depending on which party governed in Dhaka. Hasina, who served as prime minister from 1996 to 2001 and again from 2009 to 2024, maintained particularly close ties with New Delhi.In 2020, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi described bilateral ties as a “golden chapter.” Yet Hasina’s opponents frequently accused her of being overly accommodating to Indian interests.Anti-India sentiment intensified following her ouster and India’s refusal to extradite her. Relations worsened further after the killing of Osman Hadi, a prominent anti-India protest leader, which sparked demonstrations targeting Indian interests in Bangladesh.India has also raised concerns about the treatment of Bangladesh’s Hindu minority under the interim government. Diplomatic friction has spilled into sports as well: after Bangladesh requested that its T20 World Cup matches in India be relocated to Sri Lanka, the ICC expelled Bangladesh from the tournament. Pakistan later backed Bangladesh, refusing to play India in solidarity.“India suffered a major strategic setback with Hasina’s removal,” said Michael Kugelman, senior fellow for South Asia at the Atlantic Council. “New Delhi has been uneasy with an interim government it views as influenced by Jamaat and other religious actors.”Despite tensions, Modi and Yunus met last year on the sidelines of a BIMSTEC summit, where India reiterated its support for a “democratic, stable, peaceful, and inclusive Bangladesh.” How India views the electionIndia’s stakes are high.“New Delhi wants a government in Dhaka that is willing to engage constructively and is not influenced by actors it perceives as security threats,” Kugelman said.While India would be most comfortable with a BNP-led government, it has also reached out to Jamaat leaders, reflecting uncertainty about the election outcome.“India recognises that the Awami League is unlikely to return to power in the near future,” Kugelman said. “It would accept a BNP government and work to repair the relationship.” Pakistan-Bangladesh relationsSince Hasina’s removal, Pakistan has moved quickly to rebuild ties with Dhaka. Pakistani Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif met Yunus twice in 2024, and the two countries have resumed direct trade and flights for the first time in more than a decade. Defence and military dialogues have also restarted.Analysts say Pakistan sees an opportunity to expand influence by exploiting anti-India sentiment and Islamist political momentum in Bangladesh.“Pakistan wants to heighten India’s eastern security concerns by drawing closer to Dhaka,” Rejwan said, adding that Islamabad has also promoted the idea of a Bangladesh-China-Pakistan trilateral alignment. How Pakistan views the electionPakistan would welcome either a BNP or Jamaat victory, though a Jamaat-led government would be its preferred outcome, Kugelman said.A BNP government, however, would likely maintain balanced ties rather than align strongly with Islamabad. “BNP’s policy is Bangladesh first,” Rejwan noted, “which means strategic hedging rather than dependence on any single external power.” China-Bangladesh relationsChina’s influence in Bangladesh has expanded steadily, regardless of which party is in power. Under both Hasina and Yunus, Beijing has invested heavily in infrastructure, defence cooperation, and development projects. The interim government has secured more than $2.1bn in Chinese investments and loans.China has also pledged support for managing the Rohingya refugee crisis and has discussed potential defence deals, including fighter jet purchases.“Beijing adjusted quickly to the new political reality,” Rejwan said. “Sino-Bangladesh relations were strong under Hasina and are even stronger under the interim administration.” How China views the electionChina has actively engaged all major Bangladeshi political parties ahead of the polls but is not seen as favouring any single outcome.“For Beijing, political stability is paramount,” Kugelman said. “It wants to protect its investments and limit external—particularly US—influence.”Rejwan added that China prefers inclusive engagement with all political actors and is prepared to work with whichever party forms the next government. Source: Al JazeeraThe views and analysis presented here are drawn from Al Jazeera reporting.

Deeply insecure: Why Bangladeshi minorities are scared ahead of elections

Sukumar Pramanik, a Hindu teacher in Rajshahi city – about 250km (155 miles) from Bangladesh’s capital, Dhaka – says the country’s upcoming national election could be his final test of trust in politics.Electoral periods in Bangladesh have seen spikes in communal and political violence throughout the country’s history, with religious minorities often bearing the brunt amid intense political competition and social tension.Recommended StoriesBut since August 2024, and the end of former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s rule, minorities in Bangladesh have felt under siege, with reports of attacks, killings and arson against their property, even though the government insists that most incidents were not motivated by religious hate.That backdrop has intensified fears ahead of the February 12 election, despite efforts by leading political parties to reach out to minority communities. “The leaders of major parties have assured us that we will be safe before and after the vote,” Pramanik said, but faith in politicians runs low in his community at the moment.After the August 2024 uprising that led to Hasina’s ouster, mobs in several parts of the country targeted the Hindu community, many of whose members had historically voted for Hasina’s Awami League, which has long tried to claim a “secular” mantle — even though critics have accused the party of failing to prevent attacks on minorities during its long years in power, and indulging in scaremongering.Pramanik said a mob from his village attacked the Hindu community in Rajshahi’s Bidyadharpur, beating him and breaking his hand. He required surgery and spent days in hospital. “I stood in front of the mob believing they knew me and would not attack me,” he said. “They broke my hand – but more than that, they broke my heart and my trust. I had never experienced anything like this before.” Dhaka, Bangladesh — Sukumar Pramanik, a Hindu teacher in Rajshahi city – about 250km (155 miles) from Bangladesh’s capital, Dhaka – says the country’s upcoming national election could be his final test of trust in politics.Electoral periods in Bangladesh have seen spikes in communal and political violence throughout the country’s history, with religious minorities often bearing the brunt amid intense political competition and social tension.Recommended StoriesBut since August 2024, and the end of former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s rule, minorities in Bangladesh have felt under siege, with reports of attacks, killings and arson against their property, even though the government insists that most incidents were not motivated by religious hate.That backdrop has intensified fears ahead of the February 12 election, despite efforts by leading political parties to reach out to minority communities. “The leaders of major parties have assured us that we will be safe before and after the vote,” Pramanik said, but faith in politicians runs low in his community at the moment.After the August 2024 uprising that led to Hasina’s ouster, mobs in several parts of the country targeted the Hindu community, many of whose members had historically voted for Hasina’s Awami League, which has long tried to claim a “secular” mantle — even though critics have accused the party of failing to prevent attacks on minorities during its long years in power, and indulging in scaremongering.Pramanik said a mob from his village attacked the Hindu community in Rajshahi’s Bidyadharpur, beating him and breaking his hand. He required surgery and spent days in hospital. “I stood in front of the mob believing they knew me and would not attack me,” he said. “They broke my hand – but more than that, they broke my heart and my trust. I had never experienced anything like this before.”Now, sporadic attacks in recent months ahead of the election have revived those fears. According to the BHBCUC, at least 522 communal attacks were recorded in 2025, including 61 killings. The group says 2,184 incidents took place in 2024 following Hasina’s removal in August that year.Minorities are now “deeply insecure” ahead of the election, Nath said. “There is fear among everyone,” he added.The Bangladesh government disputes claims of widespread communal violence. According to official data, in 2025, authorities recorded 645 incidents involving members of minority communities. Of these, the government says, only 71 had “communal elements”, while the remainder were classified as general criminal acts. Officials argue the figures show that most incidents involving minorities were not driven by religious hostility, stressing the need to distinguish communal violence from broader law-and-order crimes.At a national level, Bangladesh faces persistent law-and-order challenges, with an average of 3,000 to 3,500 violent crime deaths each year, according to official figures.The government has also suggested that the issue has been politicised internationally, particularly by the Indian media and officials, since the fall of Hasina’s government.Rights groups, however, present different data. Ain o Salish Kendra, a prominent human rights organisation, documented 221 incidents of communal violence in 2025, including one death and 17 injuries — lower than the BHBCUC’s count, but higher than the government’s data.And the differing numbers notwithstanding, interviews with minority communities point to deep anxiety shaped by recent lived experience. ‘Not another mental trauma’Shefali Sarkar, a homemaker in Bidyadharpur in Rajshahi, saw her life turn upside down on the afternoon of August 5, 2024 — the day Hasina fled, seeking exile in India.As fears of an attack spread, most men in the community fled, leaving the women behind in their homes. Mobs primarily targeted men in the aftermath of Hasina’s ouster.“They started vandalising our house. I thought this was it – that we were going to die,” Shefali said, still visibly shaken when recalling the day. “It left a deep scar in my mind, and I have needed mental health treatment after this.”With elections approaching, Shefali said her anxiety has returned, fearing that any fresh unrest could once again make her community a target. “I cannot go through another mental trauma,” she said.Her husband, Narayan Sarkar, said the area has remained calm since the attack and that local Muslim residents and political leaders have assured them of protection. “But the fear always remains – peace can be taken away at any time,” he said.‘Unrest might spread’Not everyone is as worried.Shaymol Karmokar, from central Bangladesh’s Faridpur district, is the secretary of the local Durga Puja celebration committee. Durga Puja is a major Hindu Bengali festival, celebrated in Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal.“We have traditionally maintained strong communal harmony here over the years,” Karmokar said. “Many areas reported attacks during the uprising, but nothing happened in our locality.”He added that political leaders had actively sought minority votes and promised to ensure their safety. “We will vote and expect a peaceful election,” he said.Indeed, BNP leader Tarique Rahman — former PM Khaleda Zia’s son — has spoken of his desire to build an inclusive Bangladesh where all communities, irrespective of faith, feel safe and secure.And the Jamaat-e-Islami, the BNP’s principal challenger in the elections, has for the first time nominated a Hindu candidate, from the city of Khulna, as part of its outreach to the community.Still, in Gopalganj, where about a quarter of voters are Hindu, worries about election violence are high.In one heavily Hindu-populated constituency of the district — which is also Hasina’s birthplace — Govinda Pramanik, secretary-general of the Bangladesh Jatiya Hindu Mohajote [Bangladesh National Hindu Grand Alliance] and an independent candidate, said he was scared that “unrest might spread around this election”, he said.BHBCUC’s Nath said the government and election authorities could have done more to assuage concerns of minorities. “Even now, as the Election Commission operates, it has not once asked religious minorities what problems they are facing or what support they need,” he said.Shafiqul Alam, press secretary to Muhammad Yunus, head of Bangladesh’s interim government, however, said authorities have taken steps to protect minorities and ensure a safe election. “We have taken adequate measures so that people of all communities – minorities and majorities, followers of all faiths and identities – can vote in a festive atmosphere,” Alam told Al Jazeera. “They could not vote freely under Sheikh Hasina over the last 15 years, as the elections were rigged.”“Our priority is to ensure that everyone can vote this time,” he added, insisting that the government had consulted minority communities and addressed their concerns.Back in Bidyadharpur village in Rajshahi, Sukumar Pramanik said he was weighing these assurances carefully. “If we come under attack again,” he said, “this will be the last time I place my trust in them.” Source : Al-JazeeraPublised Date: 01 feb 2026

Engineering February: Yunus, Jamaat, and the Manufacturing of Power

A recent report in The Washington Post cited a US diplomat working in Bangladesh, claiming Washington wants to build “friendly relations” with Jamaat-e-Islami. The diplomat reportedly made the remarks in a closed-door discussion with a group of Bangladeshi women journalists on 1 December. The newspaper’s report, we are told, was built around an audio recording of that conversation.In that recording, the diplomat expressed optimism that Jamaat would perform far better in the 12 February election than it has in the past. He even suggested the journalists invite representatives of Jamaat’s student wing to their programmes and events.When the journalists raised a fear that Jamaat, if empowered, could enforce Sharia law, the diplomat’s response was striking: he said he did not believe Jamaat would implement Sharia. And even if it did, he added, Washington could respond with measures such as tariffs. He was also heard arguing that Jamaat includes many university graduates in leadership and would not take such a decision.The Washington Post further quoted multiple political analysts suggesting Jamaat could achieve its best result in history in the 12 February vote and might even end up in power.So, is this report simply the product of an “audio leak” published just 20 days before the interim government’s election? I don’t think so.First, it stretches belief that Bangladeshi journalists would secretly record a closed conversation with a US diplomat and then pass it to The Washington Post. Second, The Washington Post would almost certainly have cross-checked the audio with the diplomat concerned. If the diplomat had objected, it is hard to imagine the paper moving ahead in this way. My conclusion is blunt: this was published with the diplomat’s planning, or at least with the US embassy’s consent.Call it what it is: a soft signal. A carefully calibrated message designed to project reassurance about Jamaat and to normalise the idea of Jamaat as a legitimate future governing force.And then came the echo.At the same time, two other international outlets, Reuters and Al Jazeera, also published reports about Jamaat-e-Islami. Both pointed towards the possibility of a strong Jamaat showing in the 12 February election. Al Jazeera’s tone, heavy with praise, makes it difficult not to suspect paid campaigning. More tellingly, an Al Jazeera poll recently put Jamaat’s public support at 33.6%, compared with 34.7% for the BNP.The goal is obvious: to “naturalise” Jamaat’s pathway to power. To make what should shock the public feel ordinary. To convert the unthinkable into the plausible, and the plausible into the inevitable.Which brings us to the unavoidable question: can Jamaat really win?History says no. The highest share of the vote Jamaat ever secured in a normal election was in 1991: 12.13%. In the next three elections, Jamaat’s vote share fell to 8.68%, 4.28%, and 4.7%. In a genuinely competitive election, Jamaat is not a double-digit party.But Bangladesh is not heading into a normal election. An unelected, illegitimate interim administration is preparing a managed vote while keeping the country’s largest political party, the Awami League, effectively outside the electoral process. In that distorted arena, behind-the-scenes engineering is underway to seat Jamaat on the throne. The diplomat’s “leak”, the favourable international coverage, and the publication of flattering polls are not isolated incidents. They are the components of a single operation.If anyone doubts the direction of travel, they should remember what happened after 5 August. In his first public remarks after that date, the army chief repeatedly addressed Jamaat’s leader with reverential language, calling him “Ameer-e-Jamaat”. From that moment onwards, Jamaat has exerted an outsized, near-monopolistic influence over Bangladesh’s political field.Yes, Khaleda Zia’s illness, Tarique Rahman’s possible return, and even the prospect of Khaleda Zia’s death have periodically given the BNP a breeze at its back. But the reel and string of the political kite are now held elsewhere. Jamaat controls the tempo.And it did not happen in a vacuum. The Awami League has been driven off the streets through mob violence, persecution, repression and judicial harassment. With its principal rival forced away from political life, Jamaat has been able to present itself not merely as a participant, but as an authority.Now look at the state itself.Every major organ of power, it is argued, is being brought under Jamaat’s influence. Within the military, “Islamisation” is being used as a cover for Jamaatisation. Fifteen decorated army officers are reportedly jailed on allegations connected to the disappearance of Abdullah Hil Azmi, the son of Ghulam Azam, widely regarded as a leading figure among the razakars. Yet it remains unclear whether Azmi was even abducted at all.The judiciary, too, is described as falling almost entirely under Jamaat’s control. Key administrative positions, especially DCs, SPs, UNOs and OCs, are increasingly occupied by Jamaat-aligned officials.On campuses, the story repeats itself. Through engineered student union elections, Jamaat’s student organisation, Islami Chhatra Shibir, has established dominance in Dhaka University and other leading public universities. Even vice-chancellor appointments are described as being shaped by Jamaat-friendly influence.And while this internal consolidation accelerates, external courtship intensifies.Since August 2024, Jamaat leaders have reportedly held at least four meetings in Washington with US authorities. Their close contact with the US embassy in Bangladesh continues. Meanwhile, the British High Commissioner has held multiple meetings with Jamaat’s ameer, widely reported in the media. Jamaat’s ameer has also visited the United Kingdom recently.In short, Jamaat has reached a level of favourable conditions never seen since its founding. Not even in Pakistan, the birthplace of its ideological ecosystem.So why would sections of the Western world want Jamaat? What does the Yunus-led interim administration gain from this? What role is it playing?The answer offered here is uncompromising: the current interim government has signed multiple agreements with Western powers, particularly the United States, including an NDA arrangement and various trade deals that are described as being against public interest. Some may be public. Much remains opaque. The government wants these agreements protected. It also wants long-term leverage over Bangladesh’s politics and territory.From a broader geopolitical perspective, Bangladesh’s land matters. It sits at a strategic crossroads. For those intent on consolidating dominance in the Asia-Pacific and simultaneously containing the influence of both China and India, Bangladesh is useful. This is part of a long game.And if Jamaat, with weak popular legitimacy, can be installed in power, external agendas become easier to execute. The argument is stark: Jamaat, as a party of war criminals and anti-liberation forces, has no natural sense of accountability to Bangladesh’s soil or its people. In exchange for power, it would hand foreign actors a blank cheque.Now to Dr Yunus.The claim here is that since taking power, Yunus has already fulfilled his personal ambitions. He has rewarded loyalists with state titles and positions, creating opportunities for them to accumulate money. He has satisfied the demands of the “deep state” that installed him. In doing so, the country’s interests have been sacrificed at every step.And throughout, Jamaat has offered Yunus unconditional support.After the election, Yunus’s priority will be survival: a safe exit for himself and his circle. That is tied to securing the future of the student leaders who claim to have been the principal stakeholders of July. In this narrative, Jamaat is stepping in again. The NCP has already aligned with Jamaat. To maintain international lobbying strength, Jamaat will ensure Yunus’s safe exit. It may even install him in the presidency if that serves the arrangement.So what will the BNP do?The answer given is grim: very little. Blinded by the hunger for power, the BNP has nodded along as Yunus and his circle pushed forward actions described as hostile to the national interest. Mirza Fakhrul has publicly claimed to see Zia within Yunus. Tarique Rahman has repeatedly been seen praising Yunus. All of it, the argument goes, for a single purpose: to reach power.But the BNP, it is suggested, failed to understand the real game. At the grassroots, many of its leaders and activists have become disconnected from the public through extortion, land-grabbing and violent intimidation. Even when visible irregularities occurred in student union elections at universities, the BNP’s student wing, Chhatra Dal, either did not protest or could not.If Jamaat takes power through a staged election on 12 February, the BNP will have no meaningful recourse left.And the country?The conclusion is bleak: Bangladeshis should not expect their suffering to end any time soon. Just as a meticulously designed operation removed an elected Awami League government, another meticulous design is now being finalised to seat Jamaat-e-Islami, a party branded by the author as one of war criminals, with the backing of foreign powers.Yunus’s anti-national agreements, it is argued, will be implemented through Jamaat’s hands. Independence, sovereignty and the constitution will be thrown into the dustbin. Secularism, women’s freedom, and minority rights will be locked away in cold storage. The destination is spelled out without ambiguity:Bangladesh will become the Islamic Republic of Bangladesh.

The Cost of Politicising Academia: Lessons for Bangladesh’s Public Universities

Public universities in Bangladesh – most notably the University of Dhaka – have historically played a defining role in shaping the nation’s political and social trajectory. As a graduate of Dhaka University, I am acutely aware of its unique place in the country’s collective memory and democratic struggles. From the Language Movement of 1952 to the Liberation War of 1971, and later the anti-autocracy movements of the 1980s and 1990s, student-led activism rooted in moral conviction and the public good helped steer Bangladesh through its most critical moments. Academics often supported these struggles discreetly, preserving the university as a space for intellectual resistance rather than partisan allegiance.Even today, Dhaka University remains a critical site of resistance and political mobilisation, reasserting its role as a battleground of change during the student-led uprising of 2024. Yet this proud legacy stands in sharp contrast to the steady erosion of academic neutrality witnessed over the past three decades.Student politics gradually became an extension of mainstream party politics, with campuses and residential halls turning into partisan strongholds. Ordinary students, especially those unaffiliated with ruling factions or other political parties, were frequently marginalised, intimidated, or excluded from opportunities. What once empowered students to speak truth to power increasingly silenced them.This politicisation did not stop with students. Over the last decade, academic and administrative staff in public universities became deeply entangled in partisan networks. Many colleagues privately admitted that professional survival often depended on displaying allegiance – real or performative – to the ruling establishment. Those who remained neutral or critical risked stalled promotions, administrative sidelining, hostile work environments, or worse. As a result, universities lost the protected intellectual space necessary for genuine teaching, learning, and research.One of the most damaging consequences was the erosion of meritocracy. Academics with limited teaching engagement and little or no research record were promoted to senior ranks or influential administrative positions due to political connections rather than academic excellence. This weakened institutional leadership, demoralised capable scholars, and discouraged early-career academics from pursuing excellence. Institutional instability deepened as qualified leaders were pushed aside during political transitions.The ripple effects were profound and long-lasting. Politically aligned students were often favoured, disadvantaging neutral students and corroding trust in student–teacher relationships. Research funding and institutional investments were sometimes unevenly distributed, favouring departments with greater political leverage rather than academic need or performance. Over time, public confidence in universities began to erode, and international standing suffered as academic independence became increasingly questionable.Having studied and taught across Asia, Australia, North America, and Europe, I have rarely witnessed universities so overtly shaped by partisan loyalty. Universities elsewhere function primarily as spaces for scholarship, debate, and intellectual disagreement – not political mobilisation.A new Bangladesh offers an opportunity to reset. Public universities must be decisively de-politicised, particularly at academic and administrative levels. Healthy, issue-based student debate should be encouraged but insulated from party control. Transparent, merit-based criteria for recruitment and promotion must be restored and strictly enforced. Teaching quality, research output, leadership ability, and service to society – not political identity – should determine academic advancement.Bangladesh can learn from global best practices. Universities should promote respectful, evidence-based dialogue while rejecting intimidation and exclusion. Safeguarding intellectual freedom and open inquiry must be central to reform.Finally, sustained investment is essential: stronger funding for teaching and research, expanded international training and collaboration, merit-based scholarships, student exchange programmes, and opportunities for leading Bangladeshi academics abroad to contribute to rebuilding institutions at home. Rebuilding trust will take time, but reclaiming academic independence is the first and most necessary step towards restoring the glory, credibility, and global standing of Bangladesh’s public universities. Key Takeaways• Depoliticise universities and protect academic neutrality.• Restore merit-based recruitment and promotion.• End intimidation and partisan control on campuses.• Strengthen research, teaching, and international collaboration.• Rebuild trust and global credibility of public universities.

Mob Rule and Academic Silence: The Reconfiguration of Knowledge, Power, and the State in Bangladesh’s Universities

Over the past eighteen months, Bangladesh’s universities have experienced a disturbing rise in mob intimidation, public humiliation, physical harassment, and administrative inaction directed toward academic staff. These incidents are not isolated. They reflect a deeper reconfiguration of the relationship between the state and the knowledge system. Describing the situation as mere “campus unrest” masks its structural nature. What is unfolding is a political project designed to weaken academic authority and erode the conditions necessary for intellectual autonomy. The central question is therefore not simply who attacked whom, but whether the state still wants universities to think, or merely to comply. Under the current interim government, this violence has taken on an explicitly political character. Although the state has not imposed direct censorship, it has fostered an environment where mob pressure functions as a key instrument of governance. Repression has been socially outsourced. Mobs now serve as surrogate agents of state power, enacting forms of intimidation and control that the government itself cannot openly justify. Actions that would attract international scrutiny if undertaken directly by the state, violations of academic freedom, freedom of expression, and basic rights, are instead framed as expressions of “public anger,” “religious sentiment,” or “student demands.” This strategy, recognised in political theory as delegated repression, allows power to remain formally invisible while its coercive effects become increasingly visible and normalized. In this context, state silence is not neutrality but a political stance. When teachers are encircled, humiliated, threatened, or pressured to resign, and authorities fail to intervene, that silence functions as tacit endorsement. A government committed to protecting universities would respond with transparent investigations, institutional accountability, and firm rejection of mob coercion. Instead, we see administrative inertia and, often, surrender to street pressures. This is not accidental; it is part of a governing strategy that relies on ambiguity to avoid responsibility. A key question arises: why are academics the primary targets? Why not journalists, professionals, or other civil groups? The answer lies in the nature of academic labour. Universities produce knowledge, and knowledge can resist, disrupt, and reinterpret power. As Foucault reminds us, power and knowledge are intertwined; to control one, the other must be constrained. When teachers lose the freedom to question society, history, religion, morality, or the state, it becomes far easier for political actors to impose singular narratives. The current attacks are therefore not merely personal assaults but epistemic assaults, attempts to erode society’s capacity to think critically. Authoritarian and semi-authoritarian regimes have historically found universities threatening because they interrogate power and unsettle dominant narratives. From Nazi Germany to Latin American dictatorships and military-era Turkey, universities have been among the earliest targets of repression. Bangladesh is now witnessing a localized version of this pattern. Censorship is repackaged as “mob reaction,” and state complicity is reframed as “maintaining order.” The interim government, by failing to intervene, has effectively assumed the role of manager rather than protector. This violence also produces a dangerous moral inversion. Perpetrators no longer see themselves as aggressors but as defenders of justice. Verbal abuse, public shaming, and physical intimidation are recast as “appropriate punishment.” As Hannah Arendt warned, the banality of evil emerges when harmful acts become morally normalized. When the state refuses to challenge these distortions, it becomes complicit in them. The consequences for academic freedom are profound. Formally, teachers remain “free,” but in practice they know which topics are risky, which theories may provoke outrage, and which classroom discussions could be recorded or weaponized. Self‑censorship becomes the most effective tool of control, hollowing out the intellectual life of the university from within. Students, ultimately, bear the greatest cost. Those who learn to exercise power through intimidation today may graduate into a system where critical thinking is discouraged, curricula are diluted, and degrees lose international standing. Short-term empowerment is purchased at the price of long-term intellectual and institutional decline. In this reality, the interim government cannot evade responsibility. Protecting teachers and safeguarding academic freedom are non-negotiable duties of the state. Failure to act is not mere administrative weakness; it reflects a governing philosophy that prioritizes control over knowledge and conformity over critical thought. Where teachers are unsafe, truth is unsafe, and where truth is unsafe, the future becomes unsafe as well.

Revenge in the Name of Justice? Bangladesh’s Dangerous Return to Political Trials